For the first time, our mission was to create a zine together with a group of 12 students from Alsama project in Shatila. Alsama is the initiative of Meike Ziervogel, a German-British, who in 2020 initially founded a kind of vocational school on site. At that time, it was primarily Syrian refugee women who could learn sewing and tailoring there. Soon, the founder realized that the local need was much greater. She adapted the concept and, with a team of teachers and educators, now teaches math, Arabic, English and tailoring to more than 1,000 refugees.

Her so-called "professional class" is a group of twelve particularly gifted fourteen to 25-year-olds. The plan was to work with them to produce a magazine of about 40 pages within two weeks. The entire content was to come from our participants: they themselves were to decide which topics they wanted to report on and how they would implement these topics journalistically. That is the basic idea of Ourvoice: to give the participating young people the opportunity to tell stories from their perspective. To give them a voice.

We had held a Zoom session with some of them two weeks before the workshop to prepare for our project. Had talked about possible subject areas and also about the magazine as a medium: that it is image-driven, rich in diverse topics, and current.

Now, on the premises of Alsama in Shatila, we were finally able to meet the participants in person. 12 young people who fled Syria with their families and landed in Shatila Camp. Extremely curious and totally attentive, they seemed like dried-up sponges, soaking up everything we taught them.

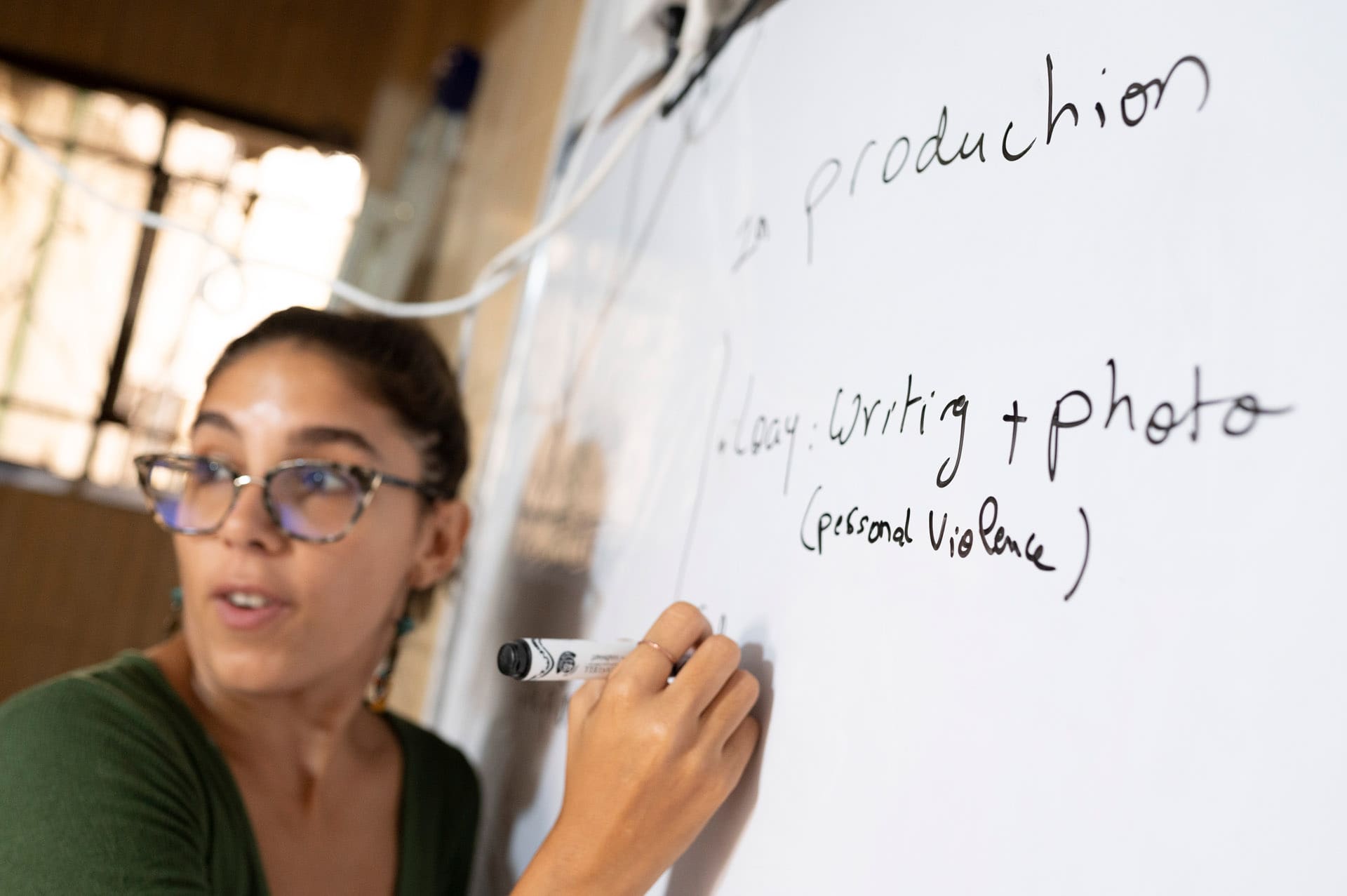

During the first three days, co-trainer Sara and I primarily taught the theoretical basics of photography and photojournalism. We combined that with practical tasks to expand on the theory. Image composition, lighting, portrait photography and the environmental portrait were our main focus areas.

We had brought ten iPhones 8 to ensure that everyone had a smartphone camera available. We had chosen iPhones to enable sharing of the photos via airdrop. This made it possible for anyone/everyone to send selected photos to our laptop at the touch of the screen. A process that had always been very time consuming and cumbersome in the past with different phones. Now it worked smoothly.

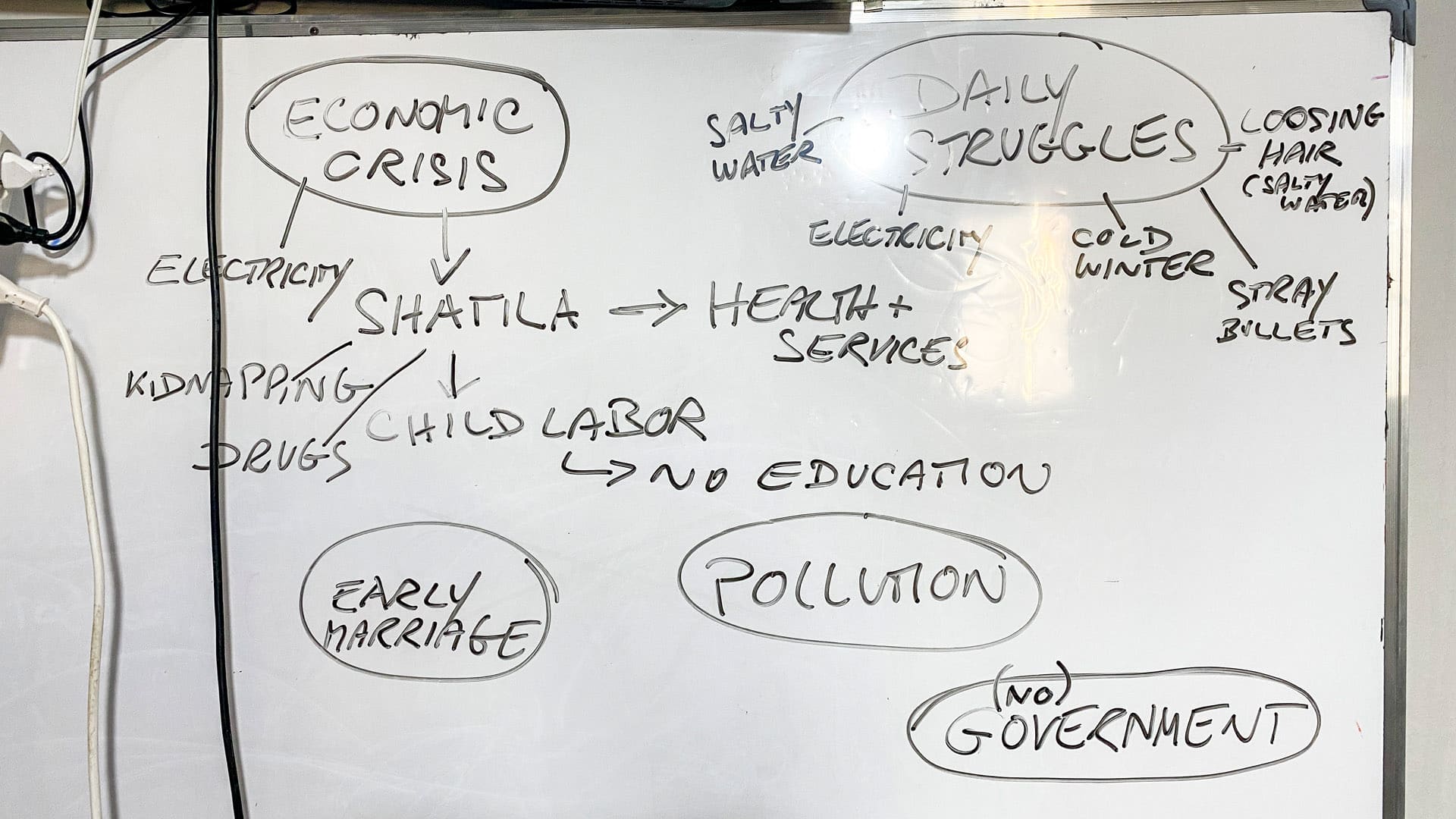

On day three, we started defining topic areas that interested the youth. This is what it looked like on our whiteboard:

Then, together with the students, we began to focus on the issues: we explained that we needed protagonists in order to be able to tell the story in a way that was appropriate for the magazine. People who were affected, willing to talk about it and to be photographed. Field research was next and our students swarmed out to find their people. We gave them an hour and a half to do so. Until lunch, which was always delivered timely at 2pm. Usually flatbread filled with chicken and lettuce with lots of mayo, plus a can of soda. The first round of field research went the way first rounds usually go: mixed. Some of our students were successful right away and found their protagonists; others came back disappointed. Sara and I encouraged them to keep searching. We explained that this is a normal process in journalism and that it is not a defeat to be rejected.

By Friday, many of our students had already photographed their first subjects and started writing their stories. That was also the day when our volunteer colleague Valentina from Berlin joined us around noon. She is a future picture editor and her task was to support their students with editing their photos on their smartphones. These photos were later transferred to our Macbook, where they were more specifically selected and - if necessary - edited. Valentina is a young, spirited Italian, speaks a few sentences of Arabic and was immediately popular with our students. She immediately started her work, viewing each student's footage directly on her phone, giving feedback and - where necessary - sending the youngsters back for more shots.

The work week ended with the feeling that we were on a good path: some had more or less strong stories they were working on, others were still looking for protagonists or again when their original heroines had cancelled. Even with the mix of subjects, we felt we had a colorful bouquet of stories. This is essential for an interesting, varied zine.

On Monday of our second week, István joined us from Munich, our designer and art director. István brings years of experience and the calmness that comes with it. His task was to teach our students the basics of magazine design on the one hand and - and this was even more important - to design our zine. We already had quite a bit of material, so he could quickly start thinking about the placement of the stories and determine lead photos together with the authors. We also had to create our cover and a zine title: a challenge because we had to print at the copy shop on Thursday in order to have our magazine ready for review on Friday. It also meant that all photos, texts and stories had to be ready by Wednesday afternoon at the latest.

We developed our own production rhythm: assessing and selecting images (Valentina), translating and editing texts from Arabic (Sara), designing pages (István), keeping an eye on the issue line and managing the time budget (Erol). Time pressure increased abruptly: a meaningful cover was urgently needed, and after some experimentation we returned to a photo that Marwa al Khodor had taken on the very first day as part of an exercise: a young person - photographed in profile - appears to be radiating a red fan of power lines through his clenched fist. An unusual eye-catcher, perfectly suited as a striking cover photo. The only thing missing was the zine title: "Shatila - Our Views" not only expressed what the zine is all about, namely the views of its authors, but also supported the photograph itself: a different view of the youths' current home.

By now it was Wednesday and a very important story was giving us a big headache. Marwa al Omar had proposed a visually promising piece about a dabke dance school in Shatila. We all had this very story at heart, because it promised to be uplifting and action-packed. A inspirational end of four zine which conained many serious articles. The problem was, Marwa had been there three times before and the school had always been closed. After a few phone calls, she learned that there would be dancing on Wednesday night starting at 6pm. Too late for our deadline.

I played a dangerous ball to István: let's finalize our magazine and wait for Marwa's photos on Wednesday evening. Maybe we could wait and see if and what the author had photographed by 7 pm. Valentina would accompany her as a coach. If we were lucky, this could be a great ending to our issue. If Marwa was unlucky, the story would die and our magazine would be four pages thinner.

Marwa and Valentina went off, Sara, István and I started proofreading loops, captions and layout corrections; the final touches in the creation of a wonderful magazine with one big problem: without Marwa's dance story, it would remain very serious. Too serious, without a positive ending. We hoped very much for good news from Valentina. And it came: it had been possible to take great photos at the dance training. We quickly chose the strongest pictures. The photo of a radiant dancing boy with arms wide open became the opening shot. A brilliant photographic conclusion to our zine. We were thrilled.

Until after midnight, we shortened stories, found the last headlines and added captions. After that, each of us read through the entire zine in parallel for errors. We went to sleep with the good feeling that we could print our zine in the copy store the next day. Print run 100.

On Thursday morning we took István's USB stick to Doculand, not far from our hotel in Beirut's party district Gemayze. After a short data check, they promised us the printed issue for the same evening - at the latest for Friday morning - our last workshop day. Those who know Lebanon know that statements like this can be fatal, because things are seen more relaxed than here in this Mediterranean country. But we had no choice but to trust ...

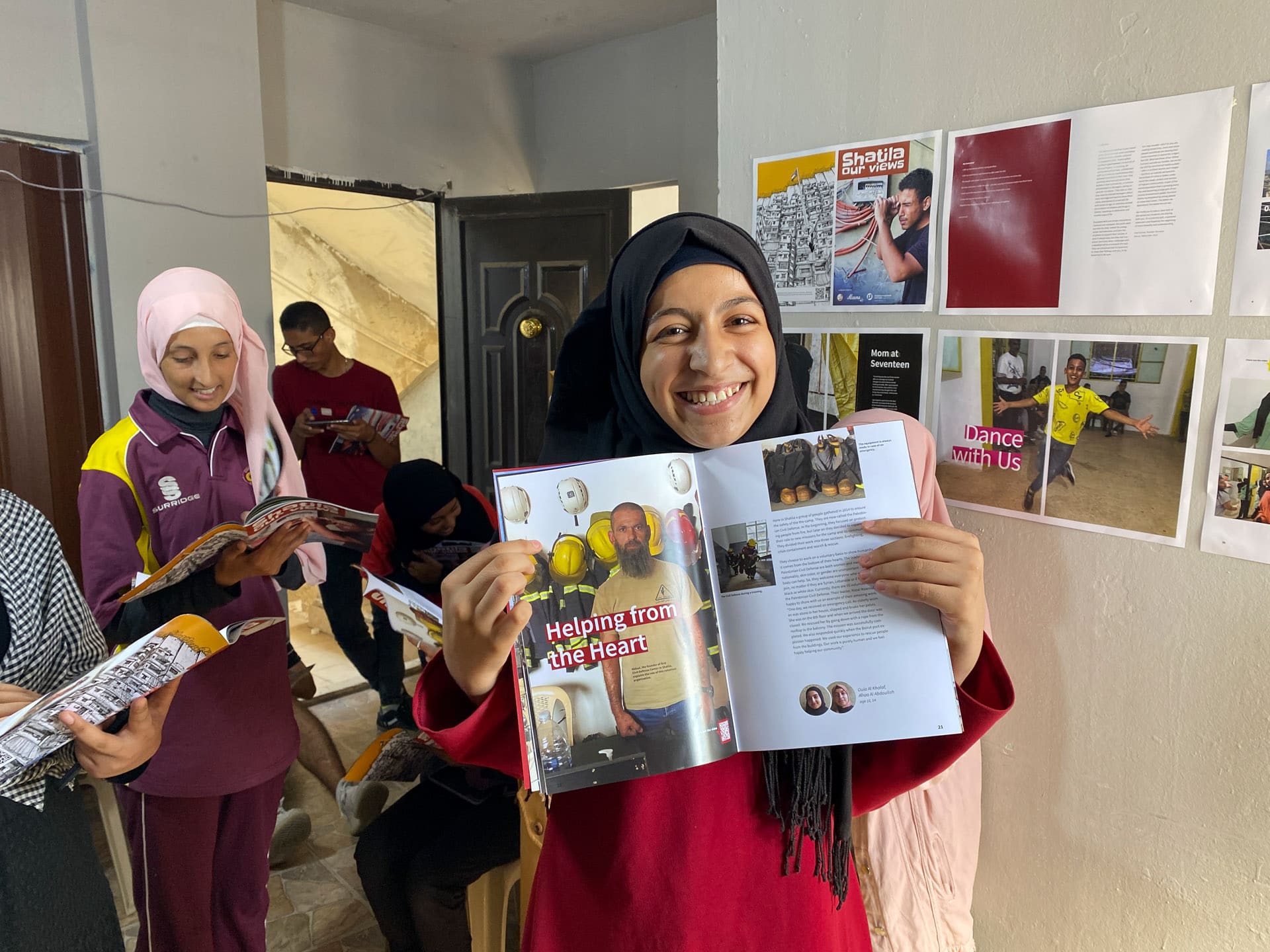

On Friday around 11 - half an hour later than planned - the printing was done and we arrived slightly late at our classroom. You could see the tension on the faces of our students: had everything worked out? Was the quality OK? Would everyone have their copy in their hands right away? We kept up the suspense as we started the critique session by posting specially printed double pages on the walls of the classroom. We did not show the zine yet.

We walked the class past the layout and analyzed their stories together: lead photos, headlines, text, captions: everything looked amazingly good.There were a few suggestions for improvement and some constructive criticism. We were all enthusiastic. Never before had the students done journalistic work on a professional level. No one had ever asked them for their opinions in pictures and text on topics such as child labor and domestic violence. Now they were faced with their own stories: some of them moved by their work, others professionally cool.

The highlight of our last day together was the distribution of the zine: now they held their work in their own hands. It was almost like a magic trick: something wonderful appeared out of nowhere. It enchanted the students. This photo of Afraa with her story shows that better than I can describe it here in the text:

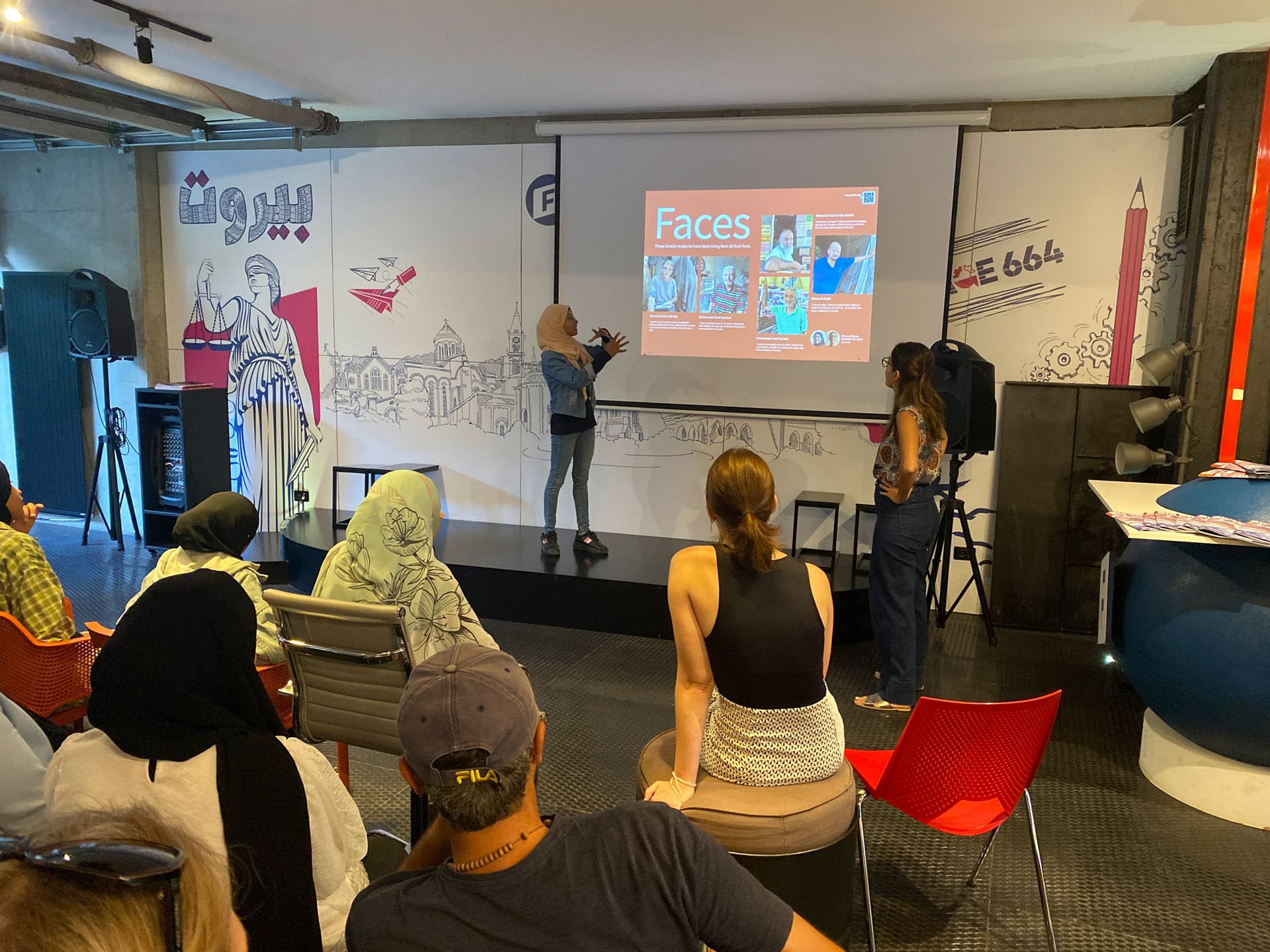

We ended our two-week project on Saturday at the premises of Friedrich Naumann Foundation in Beirut. Everyone had come and each author in turn described on the small stage how she came across her topic, why it is important to her and what the challenges were. All shared what they would take away from the workshop. That they learned how to express themselves better in writing, that they were more confident in dealing with strangers, that they learned how to tell stories with photos.

When I asked Marwa al Omar what she would take away from the project, she said something completely unexpected: she told me that until our workshop, all she ever wanted was to leave Shatila. To travel far away from this place that was loud, dirty and foreign to her. Now she has a different view of her home: "I have discovered the beauty of Shatila. Want to find more that is special and authentic here. I don't want to leave here anymore."